Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Accept Setbacks

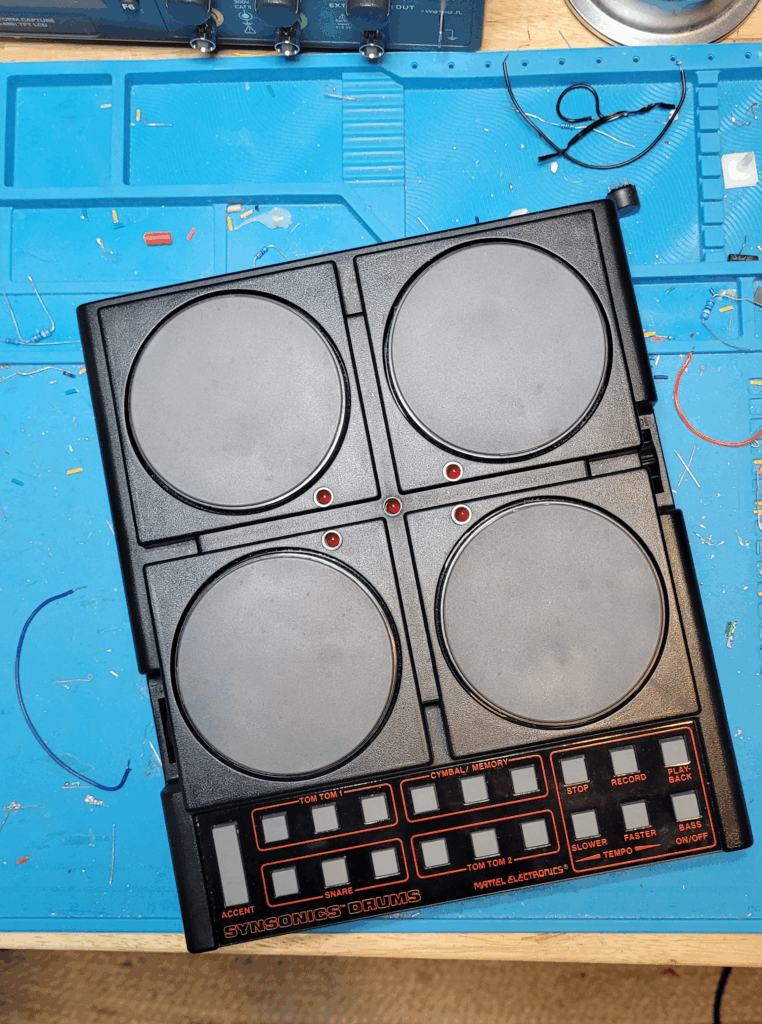

So. I have one of these. A Synsonics drum machine produced by Mattel in 1981. It’s an okay little device. Four velocity-sensitive drum pads trigger basic analog-style drum sounds–snare, cymbal, tom 1 and tom 2–with some additional buttons for playing rolls and for enabling/disabling a 4-on-the-floor kick pattern. It’s not amazing, but it has a decent sound. The only real setback is that I’m crap at playing on these little drum pads.

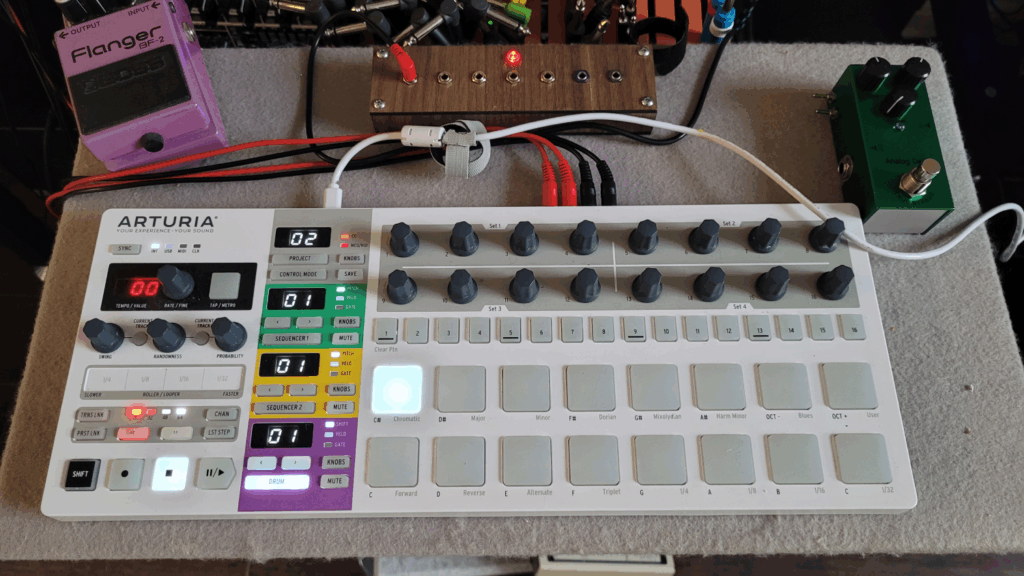

I also have one of these. I want to control ^^^that with the <<<Beatstep. It didn’t seem beyond the realm of possibility. Those drum pads are just little piezo transducers that convert the kinetic energy of the strike into electricity to trigger the drum sound. The gate outputs of the Beatstep are just little spikes of electricity used to trigger drum sounds. Right?

First, let me start by saying that I wasn’t kicking off this journey from scratch. The whole reason I bought the drum machine in the first place was because I saw a YouTube video of one that had been heavily modified. The internet was distressingly coy on quality results of documentation, so I had to dig into the internet graveyard that is the Wayback Machine to find some more details.

If you were around in the bending/modding community 20 years ago, you will have certainly heard of burnkit2600.com. Sadly, this amazing resource has gone the way of the digital dodo, so it’s difficult to track down specific information that was located there. After much poking and prodding, I was finally able to dig up this post from 2006. It was nice information, but the real gems were buried in the comments from RichardC64 (formerly of sdiy.org). This was to be the grail diary of my holy quest.

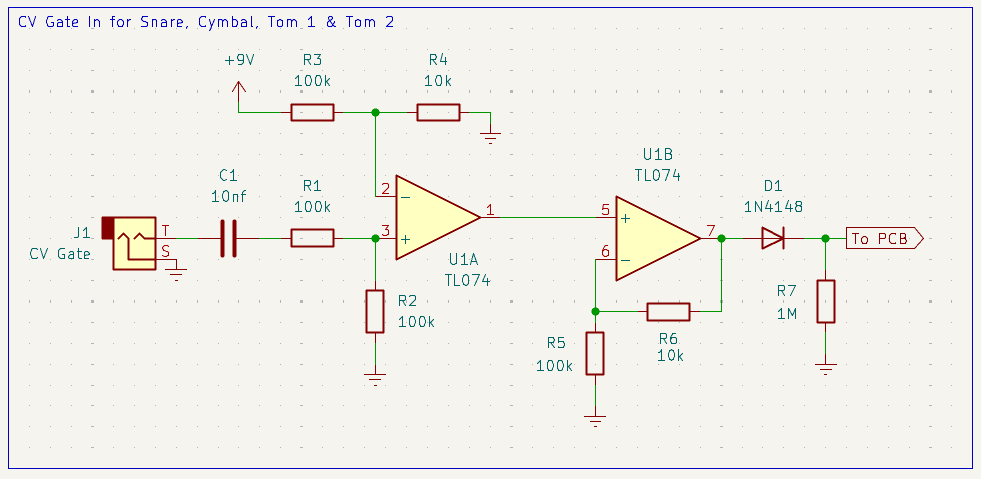

My first concern is that I had heard these drum machines were notoriously sensitive to meddling. That coupled with the fact that several of the extremely important parts of the design are long out of production and virtually unobtainable. Because of this, I wanted to be super extra careful not to feed the full 10V gate from the Beatstep straight into the drum machine.

I measured the voltage coming out of the drum pads over a variety of smacks at different degrees of whackness. Wait. I don’t think I can call it that. Let’s say it was smacks at different degrees of intensity. I was reading between 300mV and 1.2V–definitely less than 10v. I breadboarded some simple voltage dividers to drop the gate signal down to the 1V range for testing.

To test this, I needed to get the gate into the drum machine. There are a couple of places that I could tap into the circuit, but I opted for the simplest. The drum pads are connected to the circuit board through a wire harness and some header pins. Each drum pad has a ground wire and a hot wire. Inspecting the solder side of the board, it was pretty easy to identify which was which (every other pin was connected to a common trace). I soldered a short test lead to the pins not connected to the common trace.

Beatstep gate into the voltage divider into the test lead connected to the pin. Et voila? Non… I was getting something, but instead of the nice crisp drum hits, I heard a droning wash of bluuuuuuuuurrrrrrb. Neat. But not a drum machine.

It’s at this point where I had one of those moments where the brain chaos that is ADHD paused briefly enough for the facepalmingly-obvious realization: Gates are not triggers. It even says on the back of the Beatstep “Drum Gates”. Should this have been my first clue? Clearly.

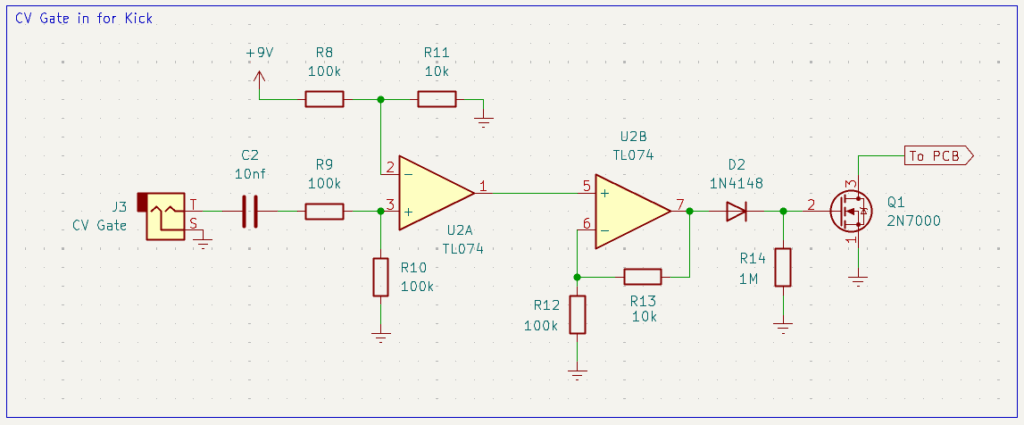

Okay. So, now I need to convert those gates to triggers. No problem. I pulled out the schematic for Keymaster and breadboarded the conversion circuit. I wanted to really, really be careful with this, so I decided to tap into the drum machine’s power supply to power the op amps. Better that than introducing another power source into the mix. Right?

Worked like a charm. It was a bit quiet, but worked exactly as I had hoped. Conceptually, this would work to trigger the snare, cymbal and both toms. There’s also a kick sound and a cymbal accent that are accessible as buttons in the control membrane, and through the DIN 5 jack on the side. Confusingly, not a MIDI jack, as this drum machine predates the universal adoption of MIDI. Allegedly, the plan was to eventually build accessories and other instruments that could interface through this jack. I just wanted to trigger the kick drum and cymbal accents.

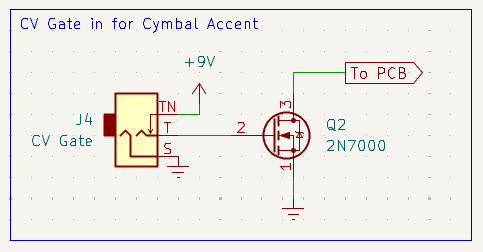

Weirdly, this wasn’t straightforward. Unlike the drum pads, which are triggered by a positive voltage spike, the kick and accent are triggered when the pins are grounded. So, I needed something that would take the voltage spike of the gate/trigger and use that to connect the pins to ground. Sounds like a job for a transistor: using the gate to open the transistor, allowing the signal from the pin to flow to ground.

It was a little wonky, but I had things close enough that I wanted to get it off the breadboard so I can do some further exploring of the circuit. Spent a few hours one grey autumn afternoon getting everything built out on protoboard and plugged everything in to give it a test. Success! I had functional snare, cymbal and toms. The kick and accent were kinda working, but I was confident I could sort out the details as I went along.

That’s when the smell hit me. If you don’t know what smell I mean, then congratulations on the charmed life you lead. Shortly after the smell hit me, the sounds stopped. Before I could pull the plug, the LEDs stopped. I let the drum machine sit for a minute while I practiced some deep breathing techniques. Then I unplugged my protoboard, powered the drum machine back up annnnndddd… Nothing.

Shoot.

Plan B

So. I have one of these. A Synsonics “Pro” drum machine produced by Mattel in 1982. It’s an okay little device. Four velocity-sensitive drum pads trigger basic analog-style drum sounds–snare, cymbal, tom 1 and tom 2–with some additional buttons for playing rolls and for enabling/disabling a 4-on-the-floor kick pattern. It’s not amazing, but it has a decent sound and an onboard battery for saving your own patterns. The only real setback is that I’m crap at playing on these little drum pads. I wanted to control it with my Beatstep.

I actually already had this. I picked it up from a local shop earlier this year, in a “Needs repair” condition. I got it home and it worked just fine. The sound was extremely noisy, but it worked. I stuck it in the drawer as a spare. In troubleshooting the first attempt, I determined that I had fried the power transformer, which is responsible for converting the +9V into both -9V and +5V. My plan was to crack open Number 2, pull out the transformer and plop it into Number 1.

Number 2 turned out to be a completely different circuit than Number 1. The entire noise-generating circuit was different. The layout was different. Components had different numbering and values. Importantly, for the sake of this story, the transformer was different. Different in a “not pin-to-pin compatible” kind of way.

Heavy sigh.

Plan C. Figure out where the triggers need to go and where to power the op amps in Number 2. This wasn’t terribly difficult, as the drum pads were still using a similar wire harness/header pin arrangement. And the power supply was roughly analogous between circuit designs. I transferred the wiring from Number 1 to Number 2, powered it up and gave it a test run.

Everything was great. We’re back in business! Now I just needed to… Oh no. There’s the smell again.

Double shoot.

That’s the second transformer fried. It’s at this stage I have to accept that this is a Me Problem™. Clearly the additional circuitry I’ve added is drawing more current than the transformer can provide, stressing a 40-year-old component to the point of failure. And, as luck would have it, this is one of those unobtainable parts. I had to face the reality that I had rendered two drum machines inoperable and my design was certainly going to do the same to any others that I tried. What to do? What to do? Give up? Well, that doesn’t play well with sunk-cost fallacy, does it? Let’s not be silly.

Faced with this reality and fully in the throes of fallacy, I needed an option. I dug through my spare parts and found a charge pump voltage inverter and a 5V regulator. What if I didn’t replace the transformer. What if I built my own power conversion circuit, beefy enough to handle all the extra load? You know what they say: When life gives you lemons, throw them away and cobble together your own transformer.

Plan D. Power transformer built. Gate-to-trigger circuits built. Everything wired up. Test… Bingpot! We’re in business and everything is working like an effing charm.

Basic Drum Triggering

Now that I have something stable and functional, let’s talk details. I’m unaware of any guides for this particular model of Synsonics Drums. Conceptually, the following modifications should work on the older version of the circuit, but the locations of these soldering points will be different. I might try this again with Number 1, if I’m able to resurrect it. If so, I’ll post an updated diagram for that one, as well.

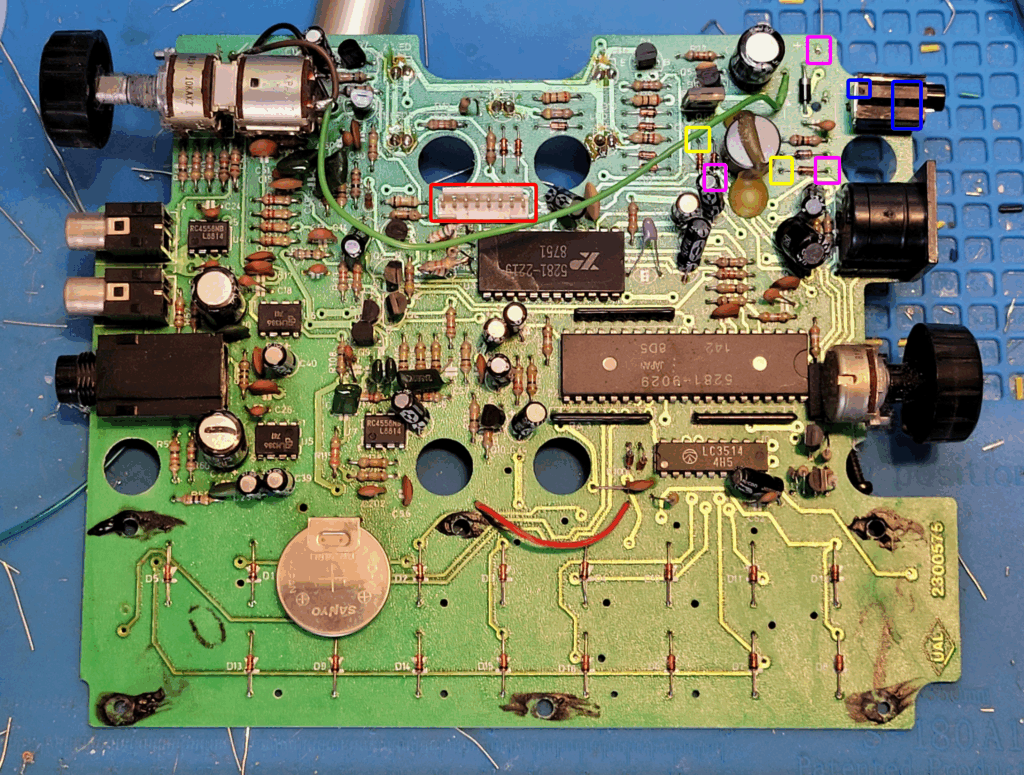

Dark Blue Box

This is the AC adapter input. The small box represents the topmost of the three solder joints. This is where you can tap into +9V. The larger box is where you can tap into ground. This is how I am powering the new transformer circuit. There’s a caveat here. Ideally, I would tap into +9V on the other side of the on/off switch (built into the volume knob). I ran into a problem doing this. The voltage drop across all the protection diodes AND in the voltage inverter resulted in a negative power rail around -7V. This was low enough that it negatively impacted operability of the device.

Yellow Box

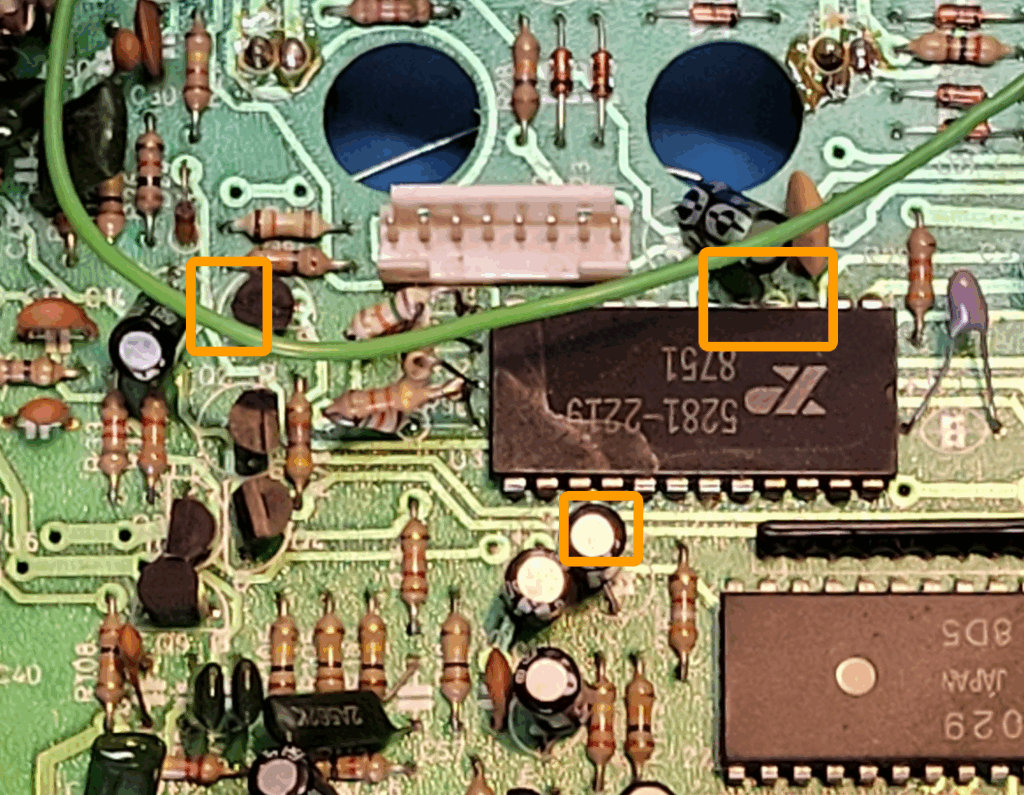

Return power supply from the transformer circuit. Wire -9V to the box on the right. Wire +5V to the box on the left. Because the power transformer is drawing power before the on/off switch, the switch doesn’t turn them off. Turning off the power kills +9V power rail, but does not kill the -9V or +5V supplies. My guess is that it’s not good to leave the circuit in that state, so I’ve opted to skip the on/off switch and just pull the plug when I’m done using the drum machine.

Purple Box

Power supply for the gate-to-trigger converters. Tap into these spots for the power needed to run the op amps. Top right is ground. Bottom right is -9V. Left is +9V.

Red Box

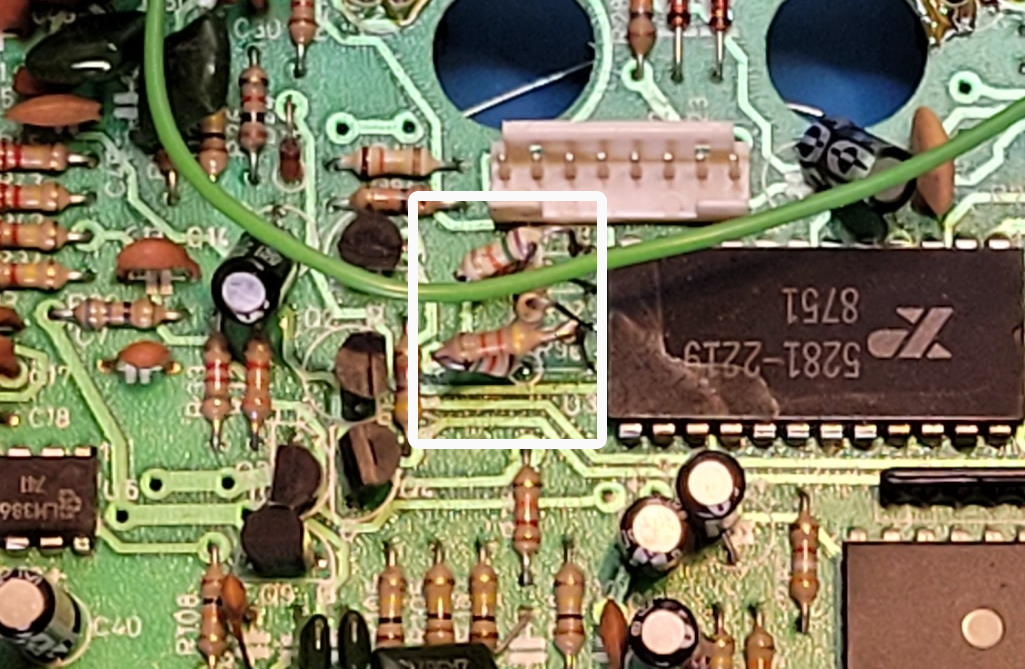

These are the header pins for the drum pad wire harness. Starting from the right, these pins are: Tom 2 trigger, ground, Tom 1 trigger, ground, Snare trigger, ground, Cymbal trigger, (you guessed it) ground. The gate-to-trigger circuit on the right converts the Beatstep gate to a lower voltage trigger. You’ll need four copies of this, where the “To PCB” of each is wired to the corresponding header pin.

This should get you up and running using an external controller, like the Beatstep, to trigger the drum sounds. If you’ve gotten this far and you haven’t destroyed anything yet, congratulations! If you want to keep pressing your luck, carry on.

Kick and Accent

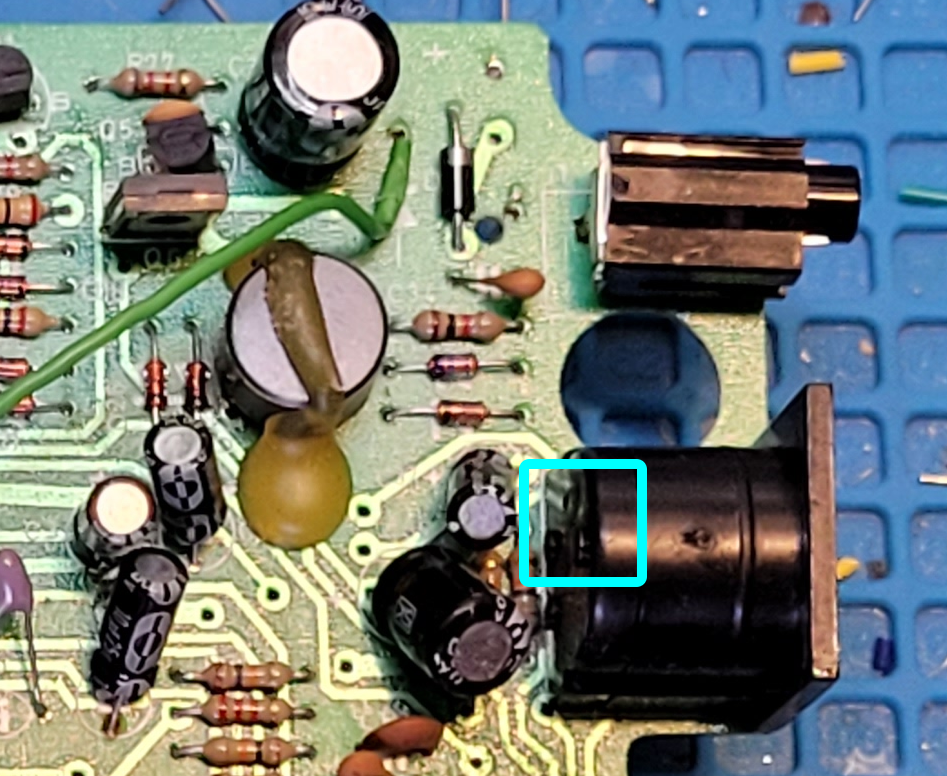

Both of these are located under the DIN 5 connector, in the light blue box. The top solder point is the kick drum and the next one down is the accent. As I mentioned above, the mechanism for triggering these sounds is different than the other four. I needed something that would connect these pins to ground at defined points in time. I opted for a simple transistor-based approach.

This is called an “accent”, but it doesn’t work the way you would typically associate with a drum accent. Rather than add some volume or oomph to the sound, it shortens the decay of the cymbal. The unaccented cymbal sounds like an open high hat or a short crash. The accented cymbal sounds more like a closed high hat. This seems backwards to me*, so I used a switched input jack to keep the transistor open when nothing is plugged in, so the cymbal defaults to the accented state.

The kick sound is really weak. It’s barely more than a click. Maybe it’s because I’m a sucker for an underdog, but I really wanted to save this sound. The transistor approach worked, but I was running into a really weird issue with timing. The kick was always a little off of the beat.

My initial thought was to blame the gate, again. So, I built another gate-to-trigger converter (and the new power supply held up!). This made things better, but still not quite right. When the pattern started on the Beatstep, the kick was in time. But, it would drift as the pattern progressed. And it would drift _in a consistent way_ every time the pattern repeated. I was really baffled by this, but found that I could minimize that drift by changing the tempo on the Synsonics. What I think might be going on here is that the kick is quantized to the tempo, so that it can never be off the beat. When it gets a trigger that’s not on the beat, it shifts it appropriately. That’s great if I’m playing with the onboard clock. Less great if I’m not.

*My suspicion is that the drum machine was built under the assumption that everyone would have a high hat accessory pedal. Purely speculation, but the easiest way I can imagine something like this working would be for the pedal to close the connection between the pin and ground. When the pedal is down, the accent is enabled, mimicking the functionality of an acoustic high hat stand.

Drum Volume

Once I got everything working and I was comfortable with the progress, I took the opportunity to start fretting over the details. Specifically, the drums weren’t that loud when triggered externally. This is especially problematic with Number 2, because of all the background hiss/noise. I was probably too cautious with the trigger voltage, in hindsight. But, I was certainly not in the headspace to redesign that (and risk blowing things up again). Instead, I made some adjustments to the limiting resistors connecting to the drum sound chip.

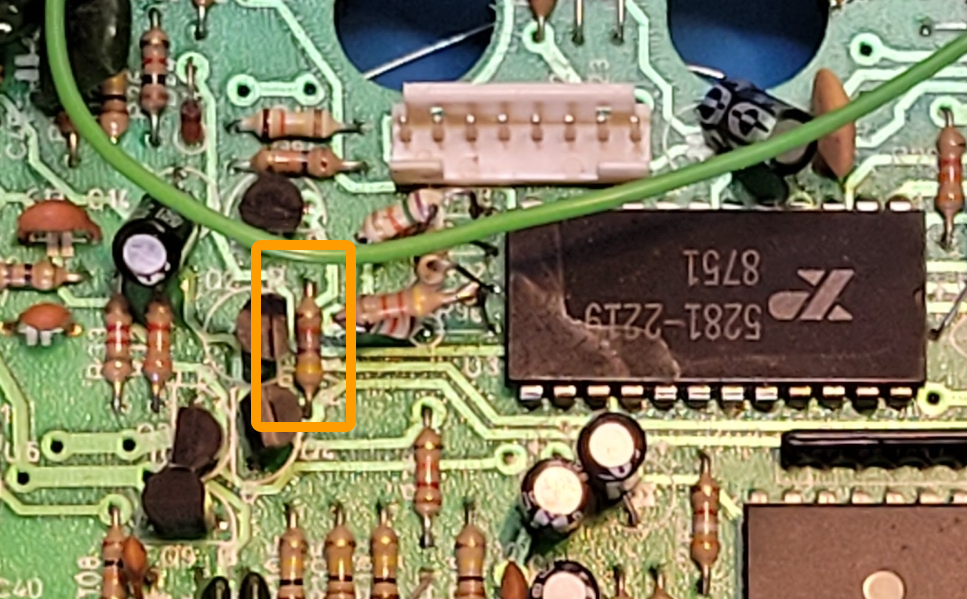

There are four resistors in the white box on the right. (Technically, there are six resistors. Two single resistors and two instances where two resistors are daisy chained to get a nonstandard value.) I replaced these resistors with new values to increase the volume of the drum sounds. These new values are to my taste. Try different values to find what works for you.

- Tom 2 (R93) replaced 153k with 22k

- Tom 1 (R92) replaced 75k with 33k

- Cymbal (R90) replaced 119k with 6.8k

- Snare (R91) replaced 75k with 8.2k

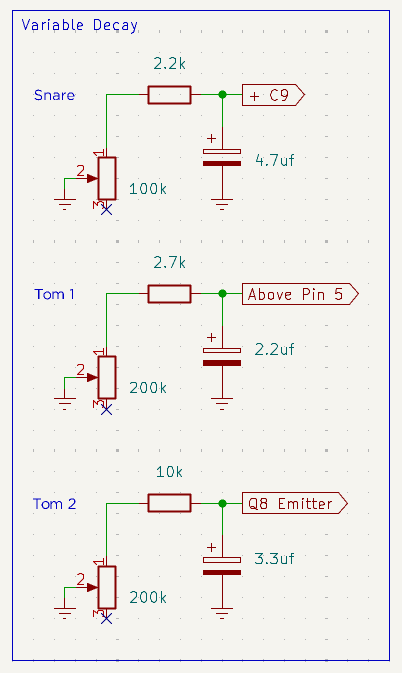

Variable Decay

Now we’re getting into the RichardC64 modifications. These are adapted from the Burnkit2600 thread linked at the beginning of this novel.

Using the circuits on the right, connect the Snare version to the positive side of C9 (bottom middle box). Tom 1 connects above pin 5, on the solder pad between C6 and C4 (top right box). There’s nothing that corresponds with this pad on the component side of the board. Tom 2 connects to the emitter of Q8 (top left box). The one on my board is marked with an “E”.

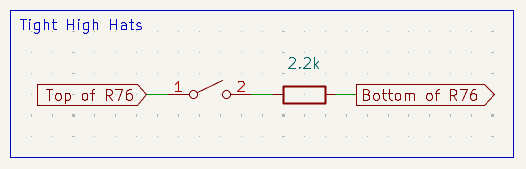

Additionally, the decay time of the high hat/cymbal can be dramatically shortened by bypassing R76 with a 2.2k resistor.

Snare Bends

I found some of my own bending points that affect the snare sound.

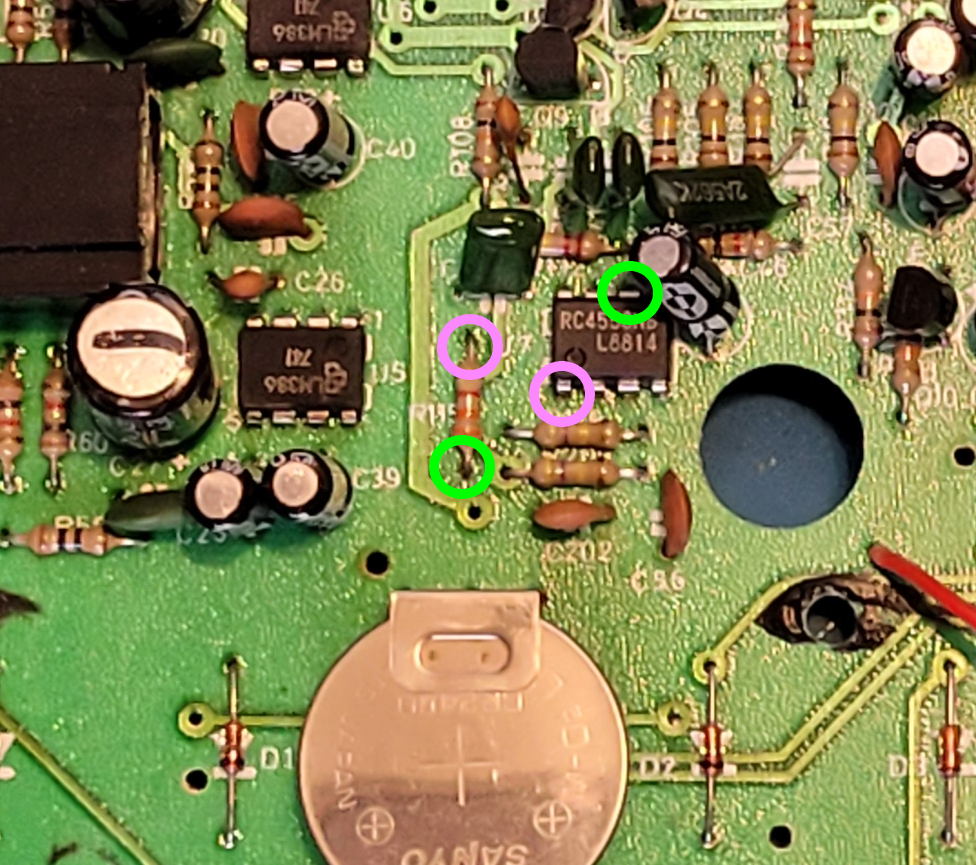

Green Circles – I’m calling this one “Ugly”. It’s a bit of a crunchy filter that also affects the cymbal. Connect pin 6 of the op amp to the bottom of R115 through a switch and 5k pot. This bend is highly sensitive to external/environmental factors. Keep the wire between pin 6 and the switch as short as possible.

Pink Circles – This changes the tone of the snare in two ways: It increases the frequency of the shell sound, while decreasing the volume of the snare sound. Connect the top of R115 to pin 1 of the op amp, through a switch and a 100k pot. This bend is less sensitive, so the wire length is less of an issue.

Nap Time

This is where I decided to call it a day**. I succeeded in turning it into a useable drum machine that can be controlled by the Beatstep. I also managed to add some additional controls to tweak the individual drum sounds, so I can add variety. I might possibly revisit this project again in the future.

**It was more like two weeks. There’s no sense in lying to you about it.

Unfinished Business

If I do revisit this, there are a few ideas that are high on my Revisit To Do List.

CV Control

I really want CV control over the decay time. This should be a dead simple vactrol implementation, but I didn’t want to mess with anything else and press my luck too far.

Output Mixer

I’m not interested in having individual outputs for each drum sound. That seems tedious to build and limited in return. I don’t plan on using it in a live setting, so if I want different effects on different drum sounds, I can just track them separately when I record. What I would like, though, is more control over the volume of each sound in the mix. Each stereo channel goes through a summing stage using an inverting op amp. I want to test replacing the input resistors for each sound with a potentiometer. Annoyingly, the resistors for one channel are under the volume/on/off switch and I didn’t feel like taking that off to access them this time around.

Noise Taming

The output is So. Very. Noisy. It seems to be coming from the summing op amp mentioned above. When poking around to find the resistors I would need to create the mixer, I noticed that the sound before the op amp was clean, but gross after. I replaced the stock 4558 with a newer TL072. This improved the sound a tad, but not enough. Each channel’s summing op amp has a small 470pf capacitor in the feedback loop–presumably to control hysteresis. My next step would be to start playing around with those to see if a more effective low pass filter does anything helpful.

Leave a Reply